Your Worst Fears About Founders (And Why You Might Be Making Them Come True)

A frank discussion about control, trust, and unintended consequences in startup governance

When your startup begins to show real traction, an interesting shift happens in conversations around control. Suddenly, there's an increasing desire for oversight, approval processes, and veto rights - even if your company is growing, profitable, and successful. It's as if the mere presence of value creates an almost instinctive grab for control.

Usually, this dynamic is connected to financing rounds, but from my perspective, it’s just because such a few companies get profitable. The reality is simple - the company becomes an asset, a valuable resource, and power games start.

What puzzled me most was the counter-intuitive nature of this phenomenon. In most business contexts, strong performance typically leads to increased autonomy. Think about your best employees - when they consistently deliver results, you give them more freedom, not less. Micromanagement is widely recognized as a motivation killer that ultimately hurts performance.

Yet in startups, we often see the opposite dynamic: the better the company performs, the stronger the push for control becomes, and, paradoxically, trust seems to diminish rather than grow. When you try to understand this pattern, you're often met with vague responses like "I just don't feel confident" - despite clear evidence of competent management and strong results.

This paradox remained a mystery to me until I encountered some fascinating findings: the drive for control often operates at a subconscious level, frequently contradicting rational economic interests. Testosterone turns on the fight for resource control for men, even if it’s not about economic interests.

More surprisingly, the data showed that female CEOs are 50% more likely to face excessive control measures than their male counterparts and 60% more likely to experience shareholder interventions. This becomes even more striking when you consider that women leaders typically implement internal control mechanisms 5.5 times more comprehensively than their male peers.

Disclaimer: I'm not suggesting that keeping founder control is always better for companies. Often, it's not. Take Oura as an example - a wonderful company where the founders primarily played the role of creating the initial product and technology. The successful business and product-market fit were achieved not by the founders but by an investor who became CEO. Oura represents one of those rare cases where there was an effective synergy between founders, investors, and professional management.

But let's set aside these underlying psychological dynamics for a moment.

What are the legitimate concerns that drive investors to seek control?

What are the real risks they're trying to mitigate?

Let's examine them one by one, because understanding these fears is the first step toward building better founder-investor relationships.

Understanding Investor Fears

Here's something rarely discussed in startup conferences: only 2% of venture capital funds generate 95% of the industry's profits. Even these top performers get it wrong 80-90% of the time. Yet instead of analyzing failures systematically, the industry often reaches for a simple solution: more control over founders.

But do control mechanisms actually address investors' real fears? Let's examine their main concerns and see if more control really helps.

#1 The "Founder Gone Wild" Fear

At its core, investors worry that successful founders will lose perspective, making increasingly risky decisions that could drive the company into irreversible losses. It's the fear that success itself might become dangerous.

The ghost of Adam Neumann and WeWork haunts every board room in Silicon Valley. And yes, the numbers are staggering: WeWork was losing $1 for every $1 of revenue, with total losses reaching $1.54 billion. Future payment obligations hit $47 billion at one point.

But here's what's interesting - let's ask two simple questions:

1. How does a company rack up such massive losses?

Simple: you need to have the money to lose in the first place. WeWork raised $22 billion in funding. Think about that number for a moment.

2. Was there ever a profitable business model?

Even at WeWork's peak valuation, they were losing $1 for every dollar of revenue. Not a single location had proven sustainable profitability.

Here's the irony: investors often push founders toward aggressive growth while simultaneously fearing its consequences.

I've experienced this firsthand. Our advertising in 2024 has a 24-hour payback period, we're profitable, and we've maintained 84% CAGR for four years straight. Yet I can see in investors' eyes in Silicon Valley that they'd prefer we were unprofitable and growing at 200% annually.

Here's a simple mechanism that could work better than blanket control: include specific financial performance triggers in your investment agreements. For example, if annual losses exceed X% of revenue, investors get increased voting power at the next board election. This gives founders a clear line they shouldn't cross and investors a concrete way to intervene if things go seriously wrong.

Think of it as a guardrail, not a steering wheel. The founder maintains control as long as they stay within reasonable financial boundaries. If they fail, they need to either convince investors they understand what went wrong and how to fix it, or accept increased investor oversight.

This would be way more effective than the current approach where investors either have too much control from the start or try to grab it when they get nervous. It's objective, measurable, and fair to both sides.

#2 The "Missing Product" Fear

This is the fear that a startup might be all smoke and mirrors – that there might not be a real product behind the impressive pitch deck. After Theranos, investors worry about being deceived by charismatic founders.

For me, this hits close to home. In investor meetings, I often see a moment of hesitation: "A woman in dark clothes doing something in health tech... reminds me of someone." Yes, Theranos. The comparison is about as subtle as a sledgehammer.

But here's what actually made Theranos possible: $724 million in investments. And not a single investor requested their own doctor to run an independent test through the Theranos system. They were satisfied with pre-fabricated demonstrations.

This pattern keeps repeating. Remember Juicero? $120 million for a juicer that squeezed pre-squeezed packets. The investors were so excited about "Keurig for juice" that nobody asked the obvious question: why can't you just squeeze these packets by hand?

Why does this happen? Three comfort traps that investors fall into:

The Pattern-Matching Illusion When we first came to Silicon Valley in 2018, every VC told us it was impossible to build a consumer health business with direct payment. That was their pattern. Now these same investors praise our consumer traction as our strongest differentiator. The problem isn't pattern-matching itself – it's confusing patterns with proof.

The Logo Effect A VC partner recently told me: "I don't know how to convince other partners, they all use Oura." Think about that: making investment decisions based on personal product preferences rather than market potential. I recently laughed reading an investment firm's blueprint justifying investing in Harvard graduates because... they had invested in lots of Harvard graduates before. Fun fact: there's actually no correlation between Nobel Prize winners and Ivy League universities. The most efficient universities in terms of Novel Prize winners are École Normale Supérieure (ENS, France) and California Institute of Technology (Caltech, USA).

The Buzzword Game Pre-ChatGPT, everyone claimed to have AI – but the backend was Excel. Now everyone has "personalization" that means nothing more than gender filters. One competitor claimed to be "personalized and AI-driven" with just 1,000 users and some ChatGPT prompts. The real question should have been: what makes you think they have anything at all?

So how do you actually verify product reality? Here's what smart investors do:

Independent Research. I personally have seen great examples: Goodwater Capital conducts user surveys and market research without the founding team's involvement. It was pretty valuable for us also; it was a new perspective, and we have great insights. Headline also uses systematic data analysis to overcome individual partner biases. They just import your data to their system and let the system provide objective opinion. That’s how we have learned that we are much more investment efficient than most other companies. It's actual due diligence, not just ticking boxes.

Reality Checks

For AI startups: Make a real deep call between experts from both sides

For "proprietary technology": Get proof of actual implementation

For data plays: Verify how data is used in decision-making processes

For market traction: Talk to actual customers by yourself if you want to invest

Anti-FOMO Protocol Before every investment, ask:

Would I invest if this exact founder came through a cold email?

Am I excited about the actual business or the social proof?

What if my competitors weren't in this deal?

Because here's the truth: control mechanisms won't save you from missing fundamental due diligence. By the time you're arguing about board seats, it's usually too late.

#3 The "Failed Management" Fear

Here's the final, deeply human fear that haunts investors: what if you have a great product, achieved product-market fit, invested the money... and then the founder loses their way?

This fear isn't entirely unfounded - 65% of venture capitalists attribute company problems to poor management. But here's what's fascinating – most of these failures happen exactly when things start working. Product-market fit achieved, millions raised, growth is good. That's when the real test begins.

Why? Because a company can only grow as fast as its founder grows – or as fast as the leader allows it to grow. And growth becomes hardest exactly when everything proves you're right.

Think about it: your founder just raised millions and hit product-market fit. Their vision worked. Their approach succeeded. Their genius is validated. For many founders, especially those with narcissistic traits, this becomes a stopping point rather than a milestone. Success cements their worldview instead of challenging it.

So what should investors actually look for? Here are the signs that your founder can scale beyond their initial success:

The Growth Test

Don't ask about "mistakes learned" – narcissists can memorize a perfect list for pitches

Instead, watch how they talk about product evolution and product market fit

Do they blame external factors for all changes, or can they admit their initial vision had flaws and they have learned something new?

Team Dynamics Everyone talks about "hiring people smarter than yourself," but here's the real test: is the top team brilliant? Get with the team to a weekly session, see it in action, or send your expert. Is the team strong enough for the future stage of growth? What is their motivation? Invest in team evaluation in the nonformal environment if you plan to invest millions.

Co-Founder Relationships Here's a stunning statistic: 65% of startups fail because of co-founder conflicts. Yet in hundreds of investor meetings, I've never been asked about reverse vesting or other legal protections between co-founders. It's like investing in a marriage without asking if there's a prenup.

The Mental Health Reality We require supervision for teachers in challenging districts but expect founders to handle constant near-death experiences without support. This makes no sense. Unless your founder is building their second or third successful startup, expecting them to handle this pressure without professional support is naive. This isn't about being nice – it's about protecting your investment. Make mental health support part of the deal. Add business coaching to the budget. Treat it as basic hygiene, not a luxury.

Team Stability Here's something radical: what if your investment agreement included team stability metrics as intervention triggers? If your best people are consistently leaving, that tells you more than any quarterly report. The team sees everything from the inside – their feet speak louder than your founder's words.

Here's what's ironic: investors worry about management capabilities declining over time, but their go-to solution – more control – often accelerates the problem. It's like trying to prevent a marriage from failing by adding more rules instead of investing in growth and communication.

The best founders aren't the ones who never make mistakes – they're the ones who can keep growing when everything suggests they don't need to anymore. That capacity for growth can't be controlled into existence. But it can be evaluated, supported, and nurtured.

Want to protect your investment? Stop obsessing about control and start thinking about capacity for growth. Because your biggest risk isn't a founder who fails – it's a founder who stops growing exactly when the company needs them to level up the most.

# What Actually Works: Moving Beyond Control

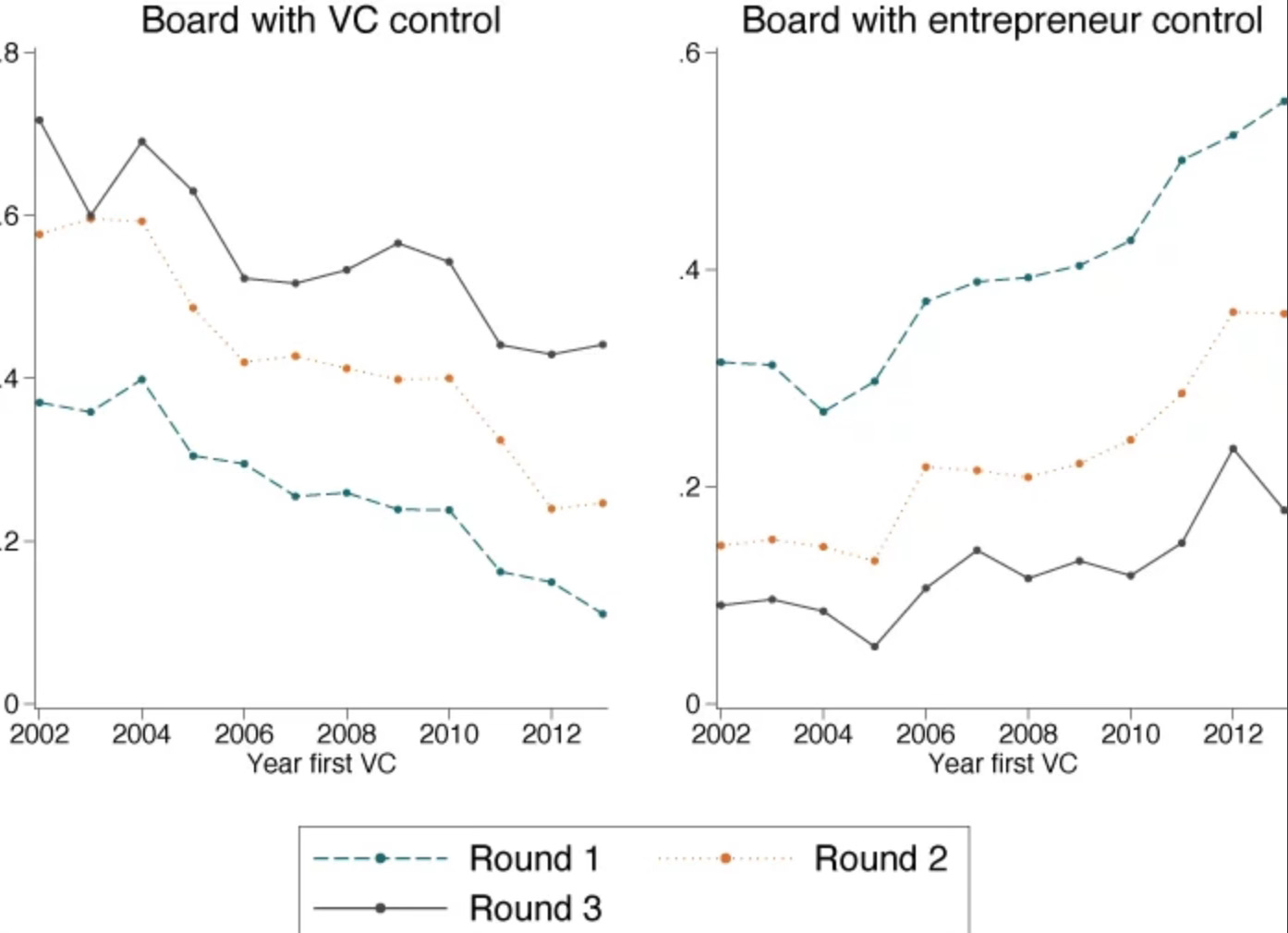

The venture industry is changing. Now dual-class shares are increasingly common among innovative companies. The data is starting to show why: founders with strong control rights tend to innovate more aggressively and make better long-term strategic decisions.

In the AI era speed of innovation will increase dramatically. It means that conservative management will lose to management who can manage in all three modes simultaneously: effective operational management for scaling, innovative product management for non stop improvements, disruption when it’s right time and opportunity.

Please remember the story of Blockbuster: their board decided not to invest in video streaming and not to buy Netflix. They were conservative. They were in control. Thet died. In AI era they would die even faster.

So, this isn't about letting founders run wild – it's about finding smarter ways to align interests and protect investments. Here's what actually works in practice:

1 Smart Triggers Instead of Blanket Control

I recently talked with a founder who told me: "Our investors set clear financial boundaries – if we exceed them, they get more voting power. It's fair, it's clear, and it actually makes me feel more confident because I know exactly where the lines are."

This approach can work better because:

- Founders know their boundaries

- Investors have clear intervention points

- Everyone can focus on building rather than politics

The key is specificity. Don't say "we need more oversight" – specify exactly what triggers increased investor involvement. Whether it's financial metrics, team stability, or customer satisfaction levels, make it measurable and objective.

2 Better Due Diligence, Not More Control

One of the most effective approaches I've seen comes from a fund that sends their industry experts to spend a week working alongside the team – not evaluating them, but actually contributing to projects. They catch more red flags in those five days than months of board meetings would reveal.

Some funds are already evolving:

- Goodwater Capital conducts independent user research

- Headline uses systematic data analysis to overcome partner biases

- Others are starting to include team stability metrics in their evaluation

3 The Founder Development Framework

Let's talk about something uncomfortable: founder mental health. Yes, I can feel investors squirming in their chairs already. Nobody wants to ask a charismatic founder if they have a therapist. Male founders might react defensively or dismiss the question entirely.

But think about it differently: what shows more maturity and reliability – a founder who pretends they're superhuman and never stressed, or one who openly acknowledges the psychological challenges of building a company and has systems in place to handle them?

I'll be direct: a founder who's comfortable talking about stress management and has a therapist isn't showing weakness – they're demonstrating emotional intelligence and self-awareness. These are exactly the qualities you want in someone handling your millions during crisis moments.

It's fascinating: we trust founders with hundreds of millions in capital, but we're uncomfortable asking them how they handle the psychological burden of that responsibility. Yet, if you look at long-term successful CEOs, many openly discuss their support systems – coaches, therapists, mentors.

This isn't about fixing broken founders. It's about recognizing that emotional maturity and willingness to seek support are actually positive indicators for investment. Just like you'd rather invest in a founder who has a CFO rather than doing their own accounting, you might want to bet on someone who has professional support for the mental challenges of the role.

The real question isn't "How do we get founders to accept therapy?" It's "Why aren't we seeing professional mental health support as a sign of maturity and reliability in leadership?"

The Way Forward

Let's drop the pretense for a moment.

Smart investors – you already know that control doesn't prevent disasters. Smart founders – you know that complete autonomy doesn't guarantee success. We're all trying to build something extraordinary in a world where 98% of venture funds don't make money, and most startups fail.

Maybe it's time for a more honest conversation. Instead of playing the usual game of founders pretending they never doubt themselves and investors pretending they can control their way to returns, what if we talked about what actually keeps us up at night?

I just saw our logo on Times Square. And you know what? Even with a business coach, a therapist, and strong metrics, I still have moments of doubt and I have to learn things on the go. Just like I'm sure investors have moments when they wonder if more control would really have prevented their past failures.

Let's start talking about our failures out loud. It’s moving there already.

So, I couldn't help but wonder: when did we decide that pretending to be perfect was safer than admitting we're all figuring this out? And if trust is really earned through honesty, why are we so afraid to be honest with each other and ourselves?